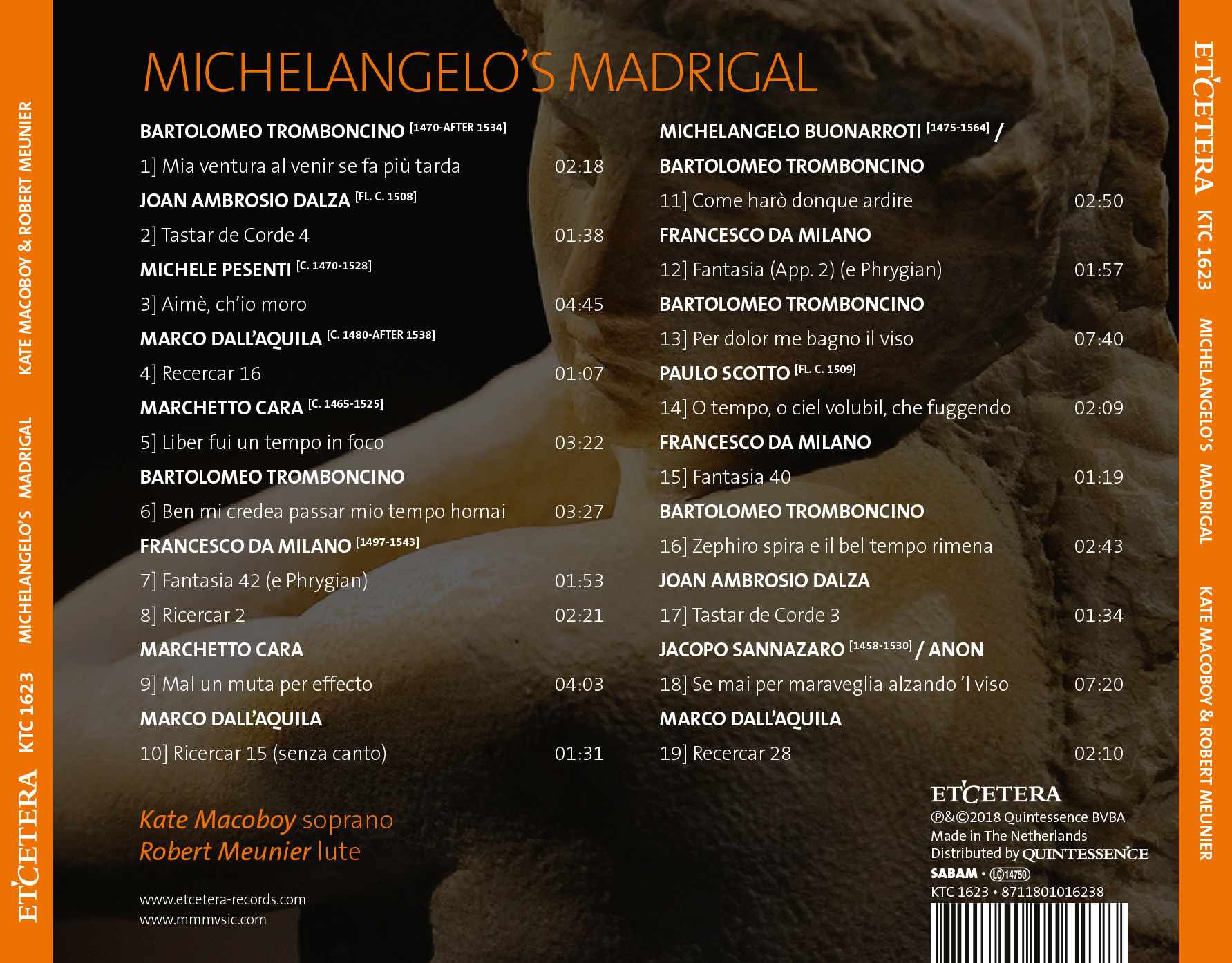

1. Mia ventura al venir se fa più tarda

Composer: Bartolomeo Tromboncino

Artist(s): Kate Macoboy, Robert Meunier

2. Tastar de corde 4

Composer: Joan Ambrosio Dalza

Artist(s): Kate Macoboy, Robert Meunier

3. Aimè, ch’io moro

Composer: Michele Pesenti

Artist(s): Kate Macoboy, Robert Meunier

4. Recercar 16

Composer: Marco Dall’Aquila

Artist(s): Kate Macoboy, Robert Meunier

5. Liber fui un tempo in foco

Composer: Marchetto Cara

Artist(s): Kate Macoboy, Robert Meunier

6. Ben mi credea passar mio tempo homai

Composer: Bartolomeo Tromboncino

Artist(s): Kate Macoboy, Robert Meunier

7. Fantasia 42 (E phrygian)

Composer: Francesco Canova da Milano

Artist(s): Kate Macoboy, Robert Meunier

8. Ricercar 2

Composer: Francesco Canova da Milano

Artist(s): Kate Macoboy, Robert Meunier

9. Mal un muta per effecto

Composer: Marchetto Cara

Artist(s): Kate Macoboy, Robert Meunier

10. Ricercar 15 (Senza canto)

Composer: Marco Dall’Aquila

Artist(s): Kate Macoboy, Robert Meunier

11. Come harò donque ardire

Composer: Bartolomeo Tromboncino/Michelangelo Buonarroti

Artist(s): Kate Macoboy, Robert Meunier

12. Fantasia (App. 2) (E phrygian)

Composer: Francesco Canova da Milano

Artist(s): Kate Macoboy, Robert Meunier

13. Per dolor me bagno il viso

Composer: Bartolomeo Tromboncino

Artist(s): Kate Macoboy, Robert Meunier

14. O tempo, o ciel volubil, che fuggendo

Composer: Paulo Scotto

Artist(s): Kate Macoboy, Robert Meunier

15. Fantasia 40

Composer: Francesco Canova da Milano

Artist(s): Kate Macoboy, Robert Meunier

16. Zephiro spira e il bel tempo rimena

Composer: Bartolomeo Tromboncino

Artist(s): Kate Macoboy, Robert Meunier

17. Tastar de corde 3

Composer: Joan Ambrosio Dalza

Artist(s): Kate Macoboy, Robert Meunier

18. Se mai per maraveglia alzando ’l viso

Composer: Anon./Jacopo Sannazaro

Artist(s): Kate Macoboy, Robert Meunier

19. Recercar 28

Composer: Marco Dall’Aquila

Artist(s): Kate Macoboy, Robert Meunier

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.